Difference between revisions of "MPI"

| (43 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

=Introduction= | =Introduction= | ||

| + | |||

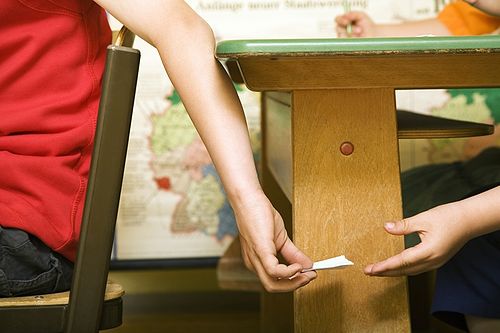

| + | [[Image:Message passing2.jpg|500px|thumbnail|center]] | ||

MPI-1[ref]--the first incarnation of the standard--arrived in 1994 in response to the need for a '''portable''' means to program the growing number of distributed memory computers appearing in the marketplace. '''MPI''' stands for '''M'''essage '''P'''assing '''I'''nterface, and as its name suggests, it is an API, rather than a new programming language. At the time of writing, MPI can be used in C, C++, Fortran-77 and Fortran-90/95 programs. We will see that MPI-1 contained little on the topic I/O. This was rectified in 1997 with the arrival of MPI-2[ref], which contained the MPI-IO standard (supporting parallel I/O) along with additional functionality to support the dynamic creation of processes and also one-sided communication models. | MPI-1[ref]--the first incarnation of the standard--arrived in 1994 in response to the need for a '''portable''' means to program the growing number of distributed memory computers appearing in the marketplace. '''MPI''' stands for '''M'''essage '''P'''assing '''I'''nterface, and as its name suggests, it is an API, rather than a new programming language. At the time of writing, MPI can be used in C, C++, Fortran-77 and Fortran-90/95 programs. We will see that MPI-1 contained little on the topic I/O. This was rectified in 1997 with the arrival of MPI-2[ref], which contained the MPI-IO standard (supporting parallel I/O) along with additional functionality to support the dynamic creation of processes and also one-sided communication models. | ||

| Line 12: | Line 14: | ||

The quintessential start. | The quintessential start. | ||

Programs in C, Fortran-77 and Fortran-90. | Programs in C, Fortran-77 and Fortran-90. | ||

| + | |||

| + | MPI_Init() and MPI_Finalise(). | ||

| + | MPI_Comm_Size() and MPI_Comm_rank(), which use the '''communicator''' MPI_COMM_WORLD. | ||

These programs assume that all processes can write to the screen. This is not a safe assumption. | These programs assume that all processes can write to the screen. This is not a safe assumption. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 22: | ||

=Send and Receive= | =Send and Receive= | ||

| − | triple (address, count, | + | Processes send their messages back to the master process, and it then prints to screen. A much safer program. |

| + | |||

| + | MPI_Send(), MPI_Recv(). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The triple (address, count, datatype) provides a pattern. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tags. Can use these as a form of filtering: junk mail, bin; handwritten & perfumed, open now!; bill, open later! | ||

| + | |||

| + | Communicators. Messages do not pass between different communicators. We can create custom communicators. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==A Common Bug== | ||

| + | |||

| + | If all processes are waiting to receive prior to sending, then we will have deadlock. See the example of a pairwise exchange. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Some Parallelisation Examples== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Numerical Integration using the Trapezoidal Rule=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | First, numerical integration using the trapezoidal rule. | ||

| + | The results we get from this program are highly sensitive to the number of CE when we have a relatively small no. of trapezoids. For example, I get a worse estimate if I run this example with 4 processes rather the 3. Can you see why? | ||

| + | ===Estimation using Monte Carlo Techniques=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Notice that the accuracy does not increase monotonically. | ||

| + | Monte Carlo techniques are suited to parallelisation. In particular, they are robust to the loss of a compute element. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Exercises== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Experiment with the free parameters (number of trapezoids, number of processes), in the numerical integration example. | ||

| + | * Experiment with the number of throws at the dartboard. What happens to the accuracy of the estimate '''on average'''? Ask yourself, how accurate do I need an estimate in order to solve my problem? | ||

| + | * What happens if the tags don't match? (ans. deadlock) | ||

| + | * Create two custom communicators: master & evens. master & odds. Write a 'chinese whispers' program that cycles messages around the two communicators in a round-robin fashion, randomly morphing a character.. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Non-Blocking Communication= | ||

==Synchronisation, Blocking and the role of Buffers== | ==Synchronisation, Blocking and the role of Buffers== | ||

| Line 24: | Line 61: | ||

Synchronised communication requires that both sender and receiver are ready. | Synchronised communication requires that both sender and receiver are ready. | ||

Through the introduction of a buffer, a sender can deposit a message before the receiver is ready. | Through the introduction of a buffer, a sender can deposit a message before the receiver is ready. | ||

| − | MPI_Recv() only returns when the message has been received, however. Hence the term blocking. | + | MPI_Recv() only returns when the message has been received, however. Hence the term blocking. |

| + | |||

| + | Having processors often idle, waiting to receive messages when they could be getting on with something useful, will degrade performance. One option is to use non-blocking send and receives. | ||

| + | |||

| + | MPI_Isend(), MPI_Irecv(). | ||

| − | + | In fact, we would like our algorithms to work as asynchronously as possible. | |

| − | + | ==Latency Hiding: first class letters, coal, canals & power stations== | |

| − | + | With increasingly parallel architectures, latency will only get worse. | |

| − | + | There will be an inevitable latency between the time a message is sent and when it is received. Say ~24hrs for a first class letter. If we sat twiddling our thumbs while we waited for the letter, we wouldn't get much done. If on the other hand, we can profitably spend our time working on something until the letter arrives, then we have effectively hidden the latency time. Think of a coal-fired power station that receives its fuel by canal barge. The barge may take a long time to travel between the pit and the boilers. If, however, the power station has a sufficient buffer, then the time spent on the canal doesn't matter. | |

=Collective Communications= | =Collective Communications= | ||

| + | |||

| + | In principle, we only need point-to-point, right? | ||

| + | However, we would lose out on a lot if we just stopped now: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * neater ways to accommodate common patterns of communication | ||

| + | * we will see efficiency gains | ||

| + | |||

| + | * MPI_Broadcast() | ||

| + | * MPI_Reduce() | ||

| + | * also Allreduce | ||

| + | |||

| + | We also introduce the useful timing function MPI_Wtime(). | ||

| + | |||

| + | example timings: | ||

| + | mpirun -np 8 ./broadcast.exe | ||

| + | rank 0: time (s) to send all the messages point-to-point = 0.617586 | ||

| + | rank 0: time (s) to broadcast the message = 0.298677 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * MPI_Scatter | ||

| + | * MPI_Gather | ||

| + | * MPI_Allgather | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note rank order. Useful for dividing up linear algebra operations, for example. | ||

==Load Balancing== | ==Load Balancing== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Broadcast-tree.pdf|600px|thumbnail|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | How does the broadcast do better than the point-to-point? | ||

| + | |||

| + | 8-process tree. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Exercises== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Try experimenting with the number of processes used in the scatter/gather example. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Sending Fewer Messages: pack and derived Types= | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several ways to construct 'derived types' (really just lists of types, counts and offsets in memory). | ||

| + | The example is of the most general method. See also indexed, vector and contiguous. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Exercises== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Write example programs highlighting the 3 other ways of making derived types in MPI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =MPI-I/O= | ||

| + | |||

| + | Introduced with MPI-2. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Concept of views (will crop up in one-sided comms too). | ||

| + | |||

| + | * MPI_File_open() & MPI_File_close() | ||

| + | * MPI_File_write() & MPI_File_read() includes familiar triplet. | ||

| + | * MPI_File_set_view() -- ned more detail on args. | ||

| + | |||

| + | MPI_COMM_SELF is the substitute communicator if opening a separate file per process. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =One-sided Communications= | ||

| + | |||

| + | NB not intrinsically faster than a send and receive operation (of course that it still happening 'under-the-hood'). Rather the benefit is to provide more flexibility when it comes to implementing algorithms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The concept of memory windows. We can think of fence calls in terms of synchronising barriers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Extended argument lists cover both the 'sender' and the 'receiver'. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * MPI_Win_create() | ||

| + | * MPI_Win_fence() | ||

| + | * MPI_Accumulate(), MPI_Put & MPI_Get() | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Exercises== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Do RMA coded programs work faster on SMP machines, than over networked CE? How does the performance compare to a send/revc equivalent? | ||

Latest revision as of 16:35, 26 July 2010

MPI: Message passing for distributed memory computing

Introduction

MPI-1[ref]--the first incarnation of the standard--arrived in 1994 in response to the need for a portable means to program the growing number of distributed memory computers appearing in the marketplace. MPI stands for Message Passing Interface, and as its name suggests, it is an API, rather than a new programming language. At the time of writing, MPI can be used in C, C++, Fortran-77 and Fortran-90/95 programs. We will see that MPI-1 contained little on the topic I/O. This was rectified in 1997 with the arrival of MPI-2[ref], which contained the MPI-IO standard (supporting parallel I/O) along with additional functionality to support the dynamic creation of processes and also one-sided communication models.

We can extend Flynn's original Taxonomy[ref] with the acronym SPMD--Single Program Multiple Data. This emphasises the fact that using e.g. MPI, we can write single programs that will execute on computers comprised of multiple compute elements, each with its own--not shared--memory space.

Hello World

The quintessential start. Programs in C, Fortran-77 and Fortran-90.

MPI_Init() and MPI_Finalise(). MPI_Comm_Size() and MPI_Comm_rank(), which use the communicator MPI_COMM_WORLD.

These programs assume that all processes can write to the screen. This is not a safe assumption.

Send and Receive

Processes send their messages back to the master process, and it then prints to screen. A much safer program.

MPI_Send(), MPI_Recv().

The triple (address, count, datatype) provides a pattern.

Tags. Can use these as a form of filtering: junk mail, bin; handwritten & perfumed, open now!; bill, open later!

Communicators. Messages do not pass between different communicators. We can create custom communicators.

A Common Bug

If all processes are waiting to receive prior to sending, then we will have deadlock. See the example of a pairwise exchange.

Some Parallelisation Examples

Numerical Integration using the Trapezoidal Rule

First, numerical integration using the trapezoidal rule. The results we get from this program are highly sensitive to the number of CE when we have a relatively small no. of trapezoids. For example, I get a worse estimate if I run this example with 4 processes rather the 3. Can you see why?

Estimation using Monte Carlo Techniques

Notice that the accuracy does not increase monotonically. Monte Carlo techniques are suited to parallelisation. In particular, they are robust to the loss of a compute element.

Exercises

- Experiment with the free parameters (number of trapezoids, number of processes), in the numerical integration example.

- Experiment with the number of throws at the dartboard. What happens to the accuracy of the estimate on average? Ask yourself, how accurate do I need an estimate in order to solve my problem?

- What happens if the tags don't match? (ans. deadlock)

- Create two custom communicators: master & evens. master & odds. Write a 'chinese whispers' program that cycles messages around the two communicators in a round-robin fashion, randomly morphing a character..

Non-Blocking Communication

Synchronisation, Blocking and the role of Buffers

Independent 'compute elements' Synchronised communication requires that both sender and receiver are ready. Through the introduction of a buffer, a sender can deposit a message before the receiver is ready. MPI_Recv() only returns when the message has been received, however. Hence the term blocking.

Having processors often idle, waiting to receive messages when they could be getting on with something useful, will degrade performance. One option is to use non-blocking send and receives.

MPI_Isend(), MPI_Irecv().

In fact, we would like our algorithms to work as asynchronously as possible.

Latency Hiding: first class letters, coal, canals & power stations

With increasingly parallel architectures, latency will only get worse.

There will be an inevitable latency between the time a message is sent and when it is received. Say ~24hrs for a first class letter. If we sat twiddling our thumbs while we waited for the letter, we wouldn't get much done. If on the other hand, we can profitably spend our time working on something until the letter arrives, then we have effectively hidden the latency time. Think of a coal-fired power station that receives its fuel by canal barge. The barge may take a long time to travel between the pit and the boilers. If, however, the power station has a sufficient buffer, then the time spent on the canal doesn't matter.

Collective Communications

In principle, we only need point-to-point, right? However, we would lose out on a lot if we just stopped now:

- neater ways to accommodate common patterns of communication

- we will see efficiency gains

- MPI_Broadcast()

- MPI_Reduce()

- also Allreduce

We also introduce the useful timing function MPI_Wtime().

example timings: mpirun -np 8 ./broadcast.exe rank 0: time (s) to send all the messages point-to-point = 0.617586 rank 0: time (s) to broadcast the message = 0.298677

- MPI_Scatter

- MPI_Gather

- MPI_Allgather

Note rank order. Useful for dividing up linear algebra operations, for example.

Load Balancing

How does the broadcast do better than the point-to-point?

8-process tree.

Exercises

- Try experimenting with the number of processes used in the scatter/gather example.

Sending Fewer Messages: pack and derived Types

Several ways to construct 'derived types' (really just lists of types, counts and offsets in memory). The example is of the most general method. See also indexed, vector and contiguous.

Exercises

- Write example programs highlighting the 3 other ways of making derived types in MPI.

MPI-I/O

Introduced with MPI-2.

Concept of views (will crop up in one-sided comms too).

- MPI_File_open() & MPI_File_close()

- MPI_File_write() & MPI_File_read() includes familiar triplet.

- MPI_File_set_view() -- ned more detail on args.

MPI_COMM_SELF is the substitute communicator if opening a separate file per process.

One-sided Communications

NB not intrinsically faster than a send and receive operation (of course that it still happening 'under-the-hood'). Rather the benefit is to provide more flexibility when it comes to implementing algorithms.

The concept of memory windows. We can think of fence calls in terms of synchronising barriers.

Extended argument lists cover both the 'sender' and the 'receiver'.

- MPI_Win_create()

- MPI_Win_fence()

- MPI_Accumulate(), MPI_Put & MPI_Get()

Exercises

- Do RMA coded programs work faster on SMP machines, than over networked CE? How does the performance compare to a send/revc equivalent?