Difference between revisions of "Subversion"

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

=Acquiring a Repository= | =Acquiring a Repository= | ||

| − | + | For the purposes of this practical, you can get yourself a repository from one of the hosting sites that can be found out in the cloud. Or you could use another repository that you have access to--perhaps hosted here in the University, some other portion of UK academia or elsewhere. I've prepared the examples using a repository accessed via the GitHub website (https://github.com). Note, however, that to obtain a free repository on GitHub, you must agree to it being readable by anyone. With that in mind, you may want to have a think about the right home for any of your intellectual property. | |

| − | + | OK, let's assume that you are happy to work with a GitHub hosted repository--at least for your initial steps learning about version control and subversion. (A natty feature of GitHub repositories is that they can be used with both Subversion and Git VCS.) | |

| + | Registering and creating a repository is easy, just follow the instructions on the webpage: | ||

[[Image:Github.png|500px|thumbnail|center|The Github web interface]] | [[Image:Github.png|500px|thumbnail|center|The Github web interface]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition to the command line client that we will describe in the following sections, you can manage your repository, view and even edit your files through the GitHub website: | ||

[[Image:Github-ggdagw-test.png|500px|thumbnail|center|A test repository]] | [[Image:Github-ggdagw-test.png|500px|thumbnail|center|A test repository]] | ||

Revision as of 11:22, 26 July 2013

Introduction

In this workshop, we'll look at using a particular Version Control System (VCS) called Subversion (often abbreviated to SVN). Before getting into the nitty-gritty of using SVN, we'll pause to consider the motivations for adopting version control and also the key concepts that are common to most available systems.

Why is Version Control useful?

OK, here's the sales pitch:

- It removes confusion about versions. For example, you will no longer have to keep inventing names for different versions of essentially the same document e.g. blah.old, blah.sav, blah.older, blah.newest2 (look familiar?).

- It makes collaborative working easier. Version control assists in coordination as it removes any confusion about versions, highlights conflicts, allows the use of independent working copies, records log messages and much more besides.

- It makes distributing your code easier. A version control repository can be visible to the world (often as a URL). However, using some highly customisable access controls, you can arrange for some (perhaps anyone) to download your project while also specifying that only a select few may be trusted to upload.

- It makes reproducing experiments easier. The ability to reproduce an experiment is a key characteristic of science. However, all too often, in the digital age, people are unable to run the same version of a model that they ran six months ago. With version control, you can always access any previous version of your model.

- It aids disaster recovery. You computer is fried? No problem! Just checkout your code to another and you're working productively again in minutes.

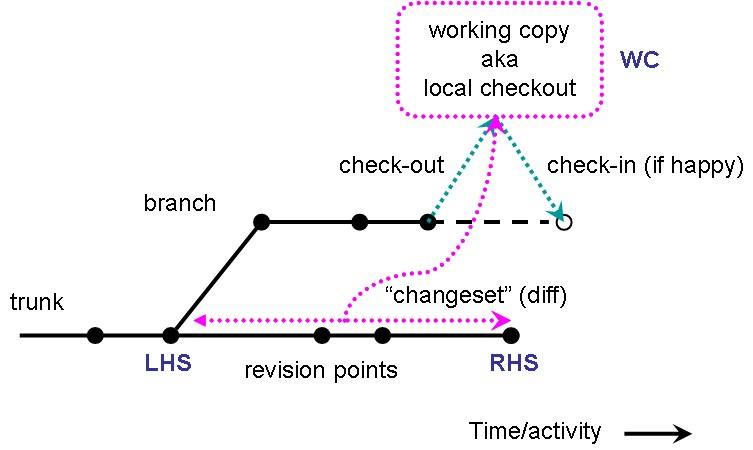

Version control concepts

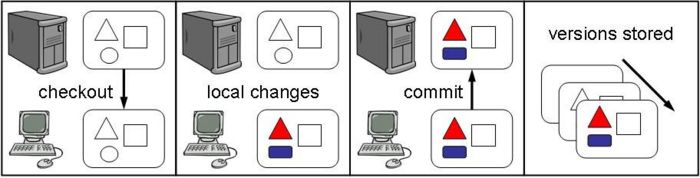

A picture can be worth a thousand words, so let's try illustrating some of the key version control concepts, before wading into acres of text:

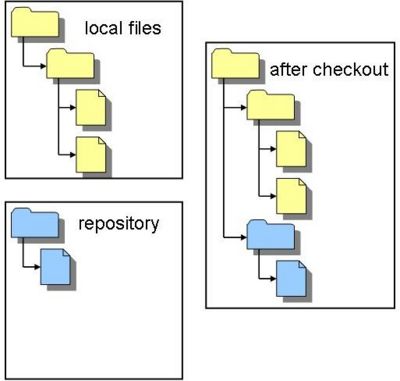

Subversion is a centralised version control system. Centralised version control means that a copy of your project is held in a central location called the repository and the subversion server logs all operations happening on the repository: every time something is changed in the repository, the server logs the time and date, the changes, the author as well as a log message. The server can be configured to give privavcy; allowing some people actions which are disallowed for others. For instance, in the practical, the server allows anonymous read-only access but only a selected number of people can changes things.

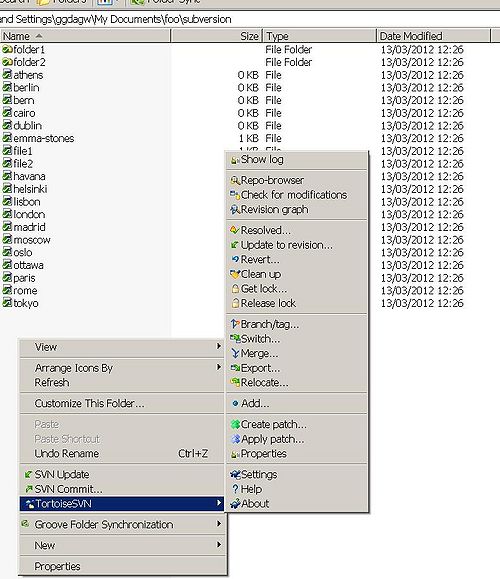

All the operations described above (logging and authentication) happen on the server. However, the server is only accessible directly to system administrators. To interact with the server, a user makes use of a subversion client. Some of you might already know about some graphical subversion clients such as TortoiseSVN (see the screen grab below). This practical will show how the command line client can be used. The subversion client can be used to (1) ask information from and (2) send information to the server. The client can also be used to get information about your working copy which is the local copy of the project that resides on your filespace. You can use the client to ask questions such as:

- which files have I modified since I last synchronised with the server?

- when was that file last modified?

- who, inadvertently, created a bug at line 18 in file foo.c?

- what has changed in that file?

Acquiring a Repository

For the purposes of this practical, you can get yourself a repository from one of the hosting sites that can be found out in the cloud. Or you could use another repository that you have access to--perhaps hosted here in the University, some other portion of UK academia or elsewhere. I've prepared the examples using a repository accessed via the GitHub website (https://github.com). Note, however, that to obtain a free repository on GitHub, you must agree to it being readable by anyone. With that in mind, you may want to have a think about the right home for any of your intellectual property.

OK, let's assume that you are happy to work with a GitHub hosted repository--at least for your initial steps learning about version control and subversion. (A natty feature of GitHub repositories is that they can be used with both Subversion and Git VCS.)

Registering and creating a repository is easy, just follow the instructions on the webpage:

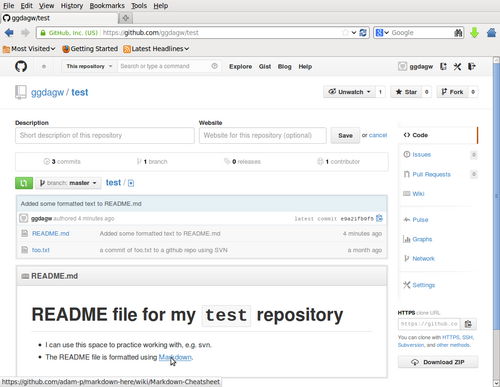

In addition to the command line client that we will describe in the following sections, you can manage your repository, view and even edit your files through the GitHub website:

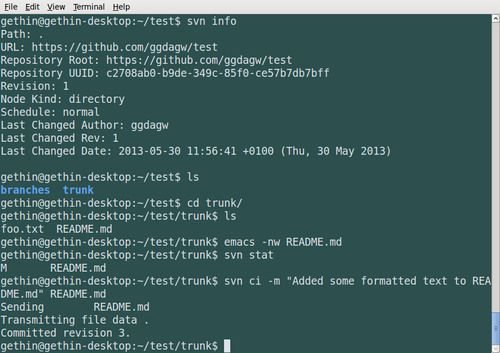

svn: the subversion command line client

The subversion command line client is called svn. To execute a subversion command, simply type:

$ svn command arguments

Some commands can also use options which are given with dashes:

svn command arguments --option optionvalue

Subversion provides extensive help about the commands to use. To get help for a particular subversion command, simply use:

$ svn help command

Getting the content for this practical

You have used the subversion client for all the practicals in the Pragmatic Programming course. To create a working copy of the repository type (first make sure you don't have a local folder called "subversion"--if you do remove it using "rm -rf subversion"):

$ svn checkout https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/subversion/trunk subversion A subversion/athens A subversion/lisbon A subversion/london A subversion/folder1 A subversion/folder1/somefile A subversion/folder2 A subversion/folder2/somefile A subversion/cairo A subversion/havana A subversion/madrid A subversion/file1 A subversion/file2 A subversion/rome A subversion/tokyo A subversion/moscow A subversion/berlin A subversion/oslo A subversion/paris

What this command does is import the content of the URL into a new folder called subversion. The letter "A" simply means that these files have been added to your working copy.

The content that you saw through your browser is now in your own file space. You may also notice hidden directories called ".svn". It is very important that you do not touch these directories.

Modifying the working copy

The working copy is yours to work with so let's go ahead and modify some things.

- To simplify the practical, only modify your given file(s), at least to start with. I'm going to work with havana. I can open that file with a text editor and add some text.

To see what files you have modified, you ask the client for the status of your working copy:

$ svn status M havana

The status shows the letter "M" for havana, indicating it has been modified.

Note that this status only shows the things that have changed in your working copy. It does not show any changes made by others, either in the repository or in their own working copies.

You can also add a new file. Create the new file using your own name. I'm going to use "newfile" in this example:

$ touch newfile $ svn status ? newfile

The question mark shows that the subversion client knows nothing about the new file (i.e. it is not currently under the auspices to version control). By default, svn will ignore new files. To indicate that a new file should be versioned, use the add command:

$ svn add newfile A newfile $ svn status M havana A newfile

Note that the letter "A" is used showing an addition.

The same things happen for deletions. Let's delete file1 for instance:

$ rm -f file1 $ svn status ! file1 M havana A newfile $ svn delete file1 D file1 $ svn status D file1 M havana

The letter "D" is used for deletions.

Subversion allows you to revert changes when you have made an error. Let's assume that file1 was deleted by error, you can get it back with:

$ svn revert file1 Reverted 'file1' $ svn status M havana A newfile

The next step is to send all these changes to the server. To avoid conflicts at this stage, make sure that you have only modified your files (i.e. your city or name). If you have modified anything else, use revert to undo your changes.

Sending changes to the repository

Sending changes to the repository is called a commit. The syntax to commit your changes is:

$ svn commit --message "Log message." --username cuba Sending havana Adding newfile Transmitting file data .. Committed revision 2.

Note that I have used cuba in this example but you should use the username (country) that you were given for the practical.

You might have noticed the revision number. You should all get different revision numbers as your commits will be done one after the other. Because you have all worked on separate files, there is no risk of conflicts and subversion will happily combine all your changes together. Have a look in websvn (refresh the page) to see the state of the repository.

Sometimes, you want a long message to go with a commit. To do this, simply execute the commit without the --message option. A text editor will then pop-up to be used to write the commit and by saving-exiting, the commit will be done. Note that svn uses the editor stored in the EDITOR environment variable, which often defaults to vi if this variable is undefined. If you are an emacs fan, set the variable first:

$ export EDITOR=emacs

(Note that you can use :q! to get out of vi, if you started it by accident. You could also set EDITOR=nano or gedit etc.)

At this stage in the practical you and others have sent changes to the server. To bring these changes back to your working copy, you need to update it.

Updating your working copy

To update your working copy, simply run:

$ svn update ... <- list of files that have been added/modified At revision X.

Again, because you have all worked on separate files, there is no risk of conflicts and subversion should fetch all the changes without problem. Your working copy contains now all the bits and pieces changed by other people. A lot neater that emailing batches files etc, no?

status, commit and update will probably be your most widely used commands:

- update regularly to bring other people's work

- status to make sure all is well

- commit frequently so that you can always recover a version you care about

However the subversion client can also be used to looks at changes in the repository and this can boost productivity.

Investigating changes

This section shows some subversion commands. Some of these commands can also be done directly from the websvn interface.

log

To get a log of what happened in the repository, use the log command. To see the files that have been modified as well as the log messages, use the --verbose option:

$ svn log --verbose ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r2 | jprenaud | 2008-05-14 15:18:44 +0100 (Wed, 14 May 2008) | 1 line Changed paths: M /trunk/file2 A /trunk/newfile First commit ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r1 | jprenaud | 2008-05-14 13:42:43 +0100 (Wed, 14 May 2008) | 2 lines Changed paths: A /trunk A /trunk/file1 A /trunk/file2 A /trunk/folder1 A /trunk/folder1/somefile A /trunk/folder2 A /trunk/folder2/somefile Initial import into the repository.

You can also invoke the log command on a particular file/path and provide a range of revisions. For instance to see which commits affected file1 between revisions 4 and 6, one could use:

$ svn log --verbose --revision 4:6 file1 ... <- log output

diff

After you have modified something, it can be handy to highlight what you've done. You can do this using the diff command.

For instance add some text to file1 and use diff to see what you have done.

$ svn diff file1

Index: file1

===================================================================

--- file1 (revision 20)

+++ file1 (working copy)

@@ -8,3 +8,4 @@

testing

purposes.

+Here are my changes, right at the end..

You can also use diff to highlight differences between two versions of some file, as stored in the repository:

$ svn diff -r73:74 havana Index: havana =================================================================== --- havana (revision 73) +++ havana (revision 74) @@ -1,4 +1,4 @@ Ring-a-Ring o'Rosies A Pocket full of Posies -"A-tishoo! A-tishoo!" +Ashes, ashes, We all fall Down!

blame (praise)

Sometimes, you want to know who wrote a particular bit of code. Subversion makes that easy with the blame command:

$ svn blame file2

2 jprenaud Added some stuff

3 jprenaud Another line

4 jprenaud A third line.

You see the content of file2 and for each line the name of the author and the revision number. You could then fetch the log message for that particular revision to get more information.

$ svn log file2 --revision 3 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ r3 | jprenaud | 2008-05-14 16:03:45 +0100 (Wed, 14 May 2008) | 1 line More things. ------------------------------------------------------------------------

Conflicts

Sometimes, a commit or an update will fail because of conflicting changes. As a rule, you should always update before a commit so the example here will show a conflict created after an update.

Creating the conflict

Let's create a conflict. This requires audience participation:

- One brave volunteer modifies file1, by adding a line, and commits the change (let's assume revision5)

- Everyone, update your working copies

- Our plucky volunteer makes more modifications to the new line

- Everyone modify the same line too

- Our volunteer commits (revision 6)

- Everyone, try to update..

The update does not immediately fail. Rather, you will be presented with some options:

Conflict discovered in 'file1'.

Select: (p) postpone, (df) diff-full, (e) edit,

(mc) mine-conflict, (tc) theirs-conflict,

(s) show all options: df

If you choose "df", then you will be presented with a summary of the 3-way difference: First how it was prior to your local change; second how it is in your working copy and lastly how it currently is in the repository. You will also be presented with the list of options again. If you choose mine-conflict, "mc", your local modifications will be preferred--at least in this working copy, since nothing has been committed back at this stage. Theirs-conflict, "tc", will prefer the repository version. If you elect to postpone, "p", then file1 is flagged with the letter "C" indicating a conflict and you will notice new files in your working copy:

$svn status ? file1.r5 ? file1.r6 ? file1.mine C file1

- file1.r5 is file1 as at revision 5 (i.e. the one at your last update)

- file1.r6 is file1 at revision 6 (i.e. the one that is on the repository now)

- file1.mine is file1 as it was in working copy before the update

- file1 contains an attempt at merging the changes (this will be similar to what you see with "df").

The last option, edit (e), will present to you the attempted merge in a text editor, for you to resolve as you see fit. Note that if you type "svn status" after editing file1 in this situation, you will see that the file is still marked as conflicted and you will not be able to commit your changes until you have resolved the conflict by typing e.g.:

svn resolved file1

Other useful commands

info

From inside a working copy, e.g.:

svn info

will give:

Path: . URL: https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/subversion/trunk Repository Root: https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/subversion Repository UUID: d9f57dc2-3d1f-4de2-a317-ca3b2cf76729 Revision: 136 Node Kind: directory Schedule: normal Last Changed Author: emma-stone Last Changed Rev: 136 Last Changed Date: 2011-10-21 16:05:07 +0100 (Fri, 21 Oct 2011)

list

svn list https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/subversion

will give:

trunk

and

svn list https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/subversion/trunk

will give:

athens berlin bern cairo dublin file1 file2 folder1/ folder2/ havana helsinki lisbon london madrid moscow oslo ottawa paris rome tokyo

move & copy

If you rename a file or directory manually, you loose its history, this is because subversion needs to be notified that a tracked file or directory will have a new name. It is simpler to use the subversion move command. For instance, to rename "file2", do:

$ svn move file2 new_file2 A new_file2 D file2

You notice that the new file is added and the old one deleted. You could have done this manually but the advantage of this is that the history of the new file before the new name is still available.

A close relation to move is copy. This creates a new file, with a copy of the revision history of it's template:

$ svn copy havana havana2 A havana2

import

When you ask for a new repository, it is empty by default. To populate it, you can use the import command. (import is because the action is done from the server, it imports something). The syntax is:

$ svn import PATH URL/trunk --message "Log message."

- PATH is the path to the local folder (by default it ses "./", i.e. the current folder)

- URL is the full URL of the repository. In the example, I also added "trunk/" at the end and the trunk would be created automatically.

mkdir and copy

Often people ask how then can create the "branches/" directory in the repository to store some specific versions of their code. This can be done by invoking mkdir directly on the server. The syntax is:

$ svn mkdir URL/branches --message "Log message."

Then you might want to create a branch of your project, for instance to call it "version1" as you start to work on version2. Here we see that we can use copy for directories, as well as files:

$ svn copy URL/trunk URL/branches/version1 --message "Creation of the version1 branch."

Then you could check out URL/branches/version1 to work on version1 rather than the trunk.

export

Sometimes, you want to get the files from the version control system but this will not be used as a working copy, for instance you are going to send the files to somebody who is not involved in the development. For instance, it is the command that was used for the Linux1 and Linux2 practicals.

You could do a checkout and remove all the hidden ".ssh" directories manually, but the easiest to to use the "export" command. It works exactly like a checkout except that you end up with a normal local folder, not a working copy. The syntax is:

$ svn export URL PATH

branching and merge

Subversion can support multiple development strands via the creation of branches. The svn copy command is used to make a (space efficient) copy of an entire file tree from, say, the trunk to a subdir called "branches". A popular reason for creating a branch is for a particular developer (or team) to work on something speculative or disruptive:

svn copy https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion/ourproject/trunk \ https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion/ourproject/branches/sally_dev \ -m "The reason why I'm branching is..."

When you have different branches in your project, you might want to merge the changes from one branch to another. For instance somebody has fixed a bug on a branch that is still present in the trunk. You might want to apply the changes done on branch back onto the trunk. Subversion allows you to do this and it is called a merge operation. We will cover this topic very quickly here but you can refer to the Subversion Red Book for more information about merging.

For example, the following command will merge in a change set from revA to revB from the sally_dev branch of ourproject into your working copy:

svn merge -r revA:revB https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion/ourproject/branches/sally_dev

You can then commit these changes--should you so desire--which will end up in the development line of whatever you chose to checkout in order to obtain your working copy.

To go further

The Subversion Red Book is the bible of subversion. Highly recommended.

In the book, you can see how to create your own repository, should you desire. For example, some simple repository setup commands will provide you with a working facility via the filesystem (i.e. the repository is on the same computer that you typically work on), or SSH (i.e. you have SSH access to the machine that will host the respository):

svnadmin create $HOME/my_test_repo

Next you might import some files (that you have stored in a directory called 'projectX'). If you're working on the same filesystem you would use:

cd projectX svn import . file://$HOME/my_test_repo/trunk -m "my import message" svn list file://$HOME/my_test_repo/trunk ...

Which--via SSH--would translate to:

cd projectX svn import . svn+ssh://user@host/absolute/path/to/my_test_repo/trunk -m "my import message" svn list svn+ssh://user@host/absolute/path/to/my_test_repo/trunk ...

NB where the components of user@host/absolute/path/to are:

- user: your username on the remote machine hosting your repository

- host: the hostname of the remote machine

- /absolute/path/to: you must specify the absolute path to your repository ($HOME will be evaluated on the machine to SSH'ing from

And you're away!

Pragmatic Programming

That's all folks. We hope you have the "Pragmatic Programming" course was useful and that you feel (at least a bit) more confident about coding on the Linux platform. Have fun.