Difference between revisions of "Profiling"

| Line 520: | Line 520: | ||

To run some equivalent C code examples. | To run some equivalent C code examples. | ||

| − | ==Expensive | + | ==Avoid Expensive Operations== |

| + | * Anything in interpreted languages, especially loops. | ||

| + | |||

* memory operations such as '''allocate''' in Fortran, or '''malloc''' in C | * memory operations such as '''allocate''' in Fortran, or '''malloc''' in C | ||

* '''sqrt''', '''exp''' and '''log''' | * '''sqrt''', '''exp''' and '''log''' | ||

* '''division''' and raising raising numbers to a '''power''' | * '''division''' and raising raising numbers to a '''power''' | ||

Revision as of 09:50, 23 July 2013

Can I speed up my program?

Introduction

Are you in the situation where you wrote a program or script which worked well on a test case but now that you scale up your ambition, your jobs are taking an age to run? If so, then the information below is for you!

Key Questions

Now that we have established that you'd like your jobs to run more quickly, here are the some key questions that you will want to address:

- How long, exactly, does my program take to run?

- Is there anything I can do to speed it up?

- Which parts of my program take up most of the execution time?

- Where should I focus my improvement efforts?

We'll get onto answering these questions in a moment. First, however, it is essential that we go into battle fully informed. The next section outlines some key concepts when thinking about program performance. These will help focus our minds when we go looking for opportunities for a speed-up.

Factors which Impact on Performance

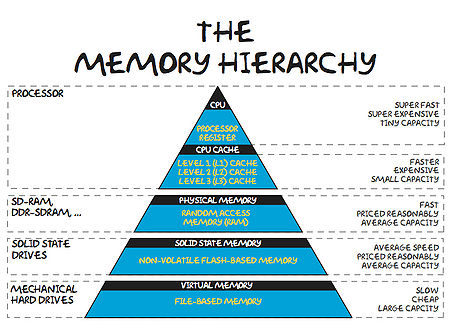

The Memory Hierarchy

These days, it takes much more time to move some data from main memory to the processor, than it does to perform operations on that data. In order to combat this imbalance, computer designers have created intermediate caches for data between the processor and main memory. Data stored at these staging posts may be accessed much more quickly than that in main memory. However, there is a trade-off, and caches have much less storage capacity than main memory.

An analogy helps us appreciate the relative differences between various storage locations:

| L1 Cache | Picking up a book off your desk (~3s) |

| L2 Cache | Getting up and getting a book off a shelf (~15s) |

| Main Memory | Walking down the corridor to another room (several minutes) |

| Disk | Walking the coastline of Britain (about a year) |

Now, it is clear that a program which is able to find the data it needs in cache will run much faster than one which regularly reads data from main memory (or worse still, disk).

How can we ensure that we make best use of the memory hierarchy?

Starting at the slowest end: Let's suppose you have a data set stored on disk which you want to work on. If that data will all fit into main memory, then it will very likely pay dividends to read all this data at the outset, work on it, and then save out any results to disk at the end. This is especially true if you will access all of the data items more than once or will have a non-contiguous pattern of access.

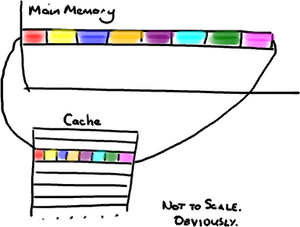

Ensuring that we make best use of cache is a little more subtle. In order to devise a good strategy, we must appreciate some of the hidden details of the inner workings of a computer: Let's say a program requests to read a single item from memory. First, the computer will look for the item in cache. If the data is not found in cache, it will be fetched from main memory, so as to create a more readily accessible copy. Single items are not fetched, however. Instead chunks of data are copied into cache. The size of this chunk matches the size of a block of storage in cache known as a cache line (often 64 bytes in today's machines). The situation is a little more complex when writing, as we have to ensure that both cache and main memory are synchronised, but--in the interests of brevity--we'll skip over this just now.

The pay-off for this chunked approach is that if the program now requests to read another item from memory, and that item was part of the previous fetch, then it will already be in cache and an slow journey to main memory will be avoided. Thus we can see that re-use of data already in cache will be a key factor in program performance.

A good example of this would be a looping situation. A loop order which predominately cycles over items already in cache will run much faster than one which demands that cache is constantly refreshed. Another point to note is that cache size is limited, so a loop cannot access many large arrays with impunity. Using too many arrays in a single loop will exhaust cache capacity and force evictions and subsequent re-reads of essential items.

Optimising Compilers

Compilers take the (often English-like) source code that we write and convert it into a binary code that can be comprehended by a computer. However, this is no trivial translation. Modern optimising compilers can essentially re-write large chunks of your code, keeping it semantically the same, but in a form which will execute much, much faster (we'll see examples below). To give some examples, they will spit of join loops, they will hoist repeated, invariant calculations out of loops, re-phrase your arithmetic etc. etc.

In short, they are very, very clever. And it does not pay to second guess what your compiler will do. It is sensible to:

- Use all the appropriate compiler flags you can think of (see e.g. https://www.acrc.bris.ac.uk/pdf/compiler-flags.pdf) to make your code run faster, but also to:

- Use a profiler to determine which parts of your executable code (i.e. post compiler transformation) are taking the most time.

That way, you can target any improvement efforts on areas that will make a difference!

Exploitation of Modern Processor Architectures

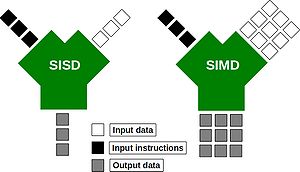

Just like the compilers described above. Modern processors are complex beasts! Over recent years, they have been evolving so as to provide more number crunching capacity, without using more electricity. One way in which they can do this is through the use of wide registers and the so-called SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) execution model:

Wide-registers allow several data items of the same type to be stored, and more importantly, processed together. In this way, a modern SIMD processor may be able to operate on 4 double-precision floating point numbers concurrently. What this means for you as a programmer, is that if you phrase your loops appropriately, you may be able to perform several of your loop interactions at the same time. Possibly saving you a big chunk of time.

Suitably instructed (often -O3 is sufficient), those clever-clog compilers will be able to spot areas of code that can be run using those wide registers. The process is called vectorisation. Today's compilers can, for example, vectorise loops with independent iterations (i.e. no data dependencies from one iteration to the next). You should also avoid aliased pointers (or those that cannot be unambiguously identified as un-aliased).

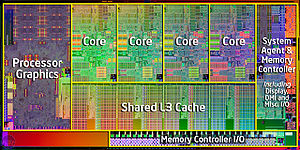

Modern processors have also evolved to have several (soon to be many!) CPU cores on the same chip:

Many cores means that we can invoke many threads or processes, all working within the same, shared memory space. Don't forget, however, that if these cores are not making the best use of the memory hierarchy, or there own internal wide-registers, you will not be operating anywhere near the full machine capacity. So you are well advised to consider the above topics before racing off to write parallel code.

Tools for Measuring Performance

OK, let's survey the territory of tools to help you profile your programs.

time

First off, let's consider the humble time command. This is a good tool for determining exactly how long a program takes to run. For example, I can time a simple Unix find command (which looks for all the files called README in the current and any sub-directories):

time find . -name "README" -print

The output (after a list of all the matching files that it found) was:

real 0m16.080s user 0m0.248s sys 0m0.716s

The 3 lines of output tell us:

- real: is the elapsed time (as read from a wall clock),

- user: is the CPU time used by my process, and

- sys: is the CPU time used by the system on behalf of my process.

Interestingly, in addition to just the total run time, find has also given us some indication of where the time is being spent. In this case, the CPU is very low compared to the elapsed time, as the process has spent the vast majority of time waiting for reads from disk.

gprof

Next up, the venerable gprof. This allows us to step up to a proper profiler. First, we must compiler our code with a suitable flag, -pg for the GNU (and many other) compilers. (We'll see what the other flags do later on.)

gcc -O3 -ffast-math -pg d2q9-bgk.c -o d2q9-bgk.exe

Once compiled, we can run our program normally:

./d2q9-bgk.exe

A file called gmon.out will be created as a side-effect. (Note also that the run-time of your program may be significantly longer when compiled with the -pg flag). We can interrogate the profile information by running:

gprof d2q9-bgk.exe gmon.out | less

This will give us a breakdown of the functions within the program (ranked as a fraction of their parent function's runtime).

Flat profile: Each sample counts as 0.01 seconds. % cumulative self self total time seconds seconds calls ms/call ms/call name 49.08 31.69 31.69 10000 3.17 3.17 collision 33.87 53.56 21.87 10000 2.19 2.19 propagate 17.13 64.62 11.06 main 0.00 64.62 0.00 1 0.00 0.00 initialise 0.00 64.62 0.00 1 0.00 0.00 write_values

gprof is an excellent program, but suffers the limitation of only being able to profile serial code (i.e. you cannot use gprof with threaded code, or code that spawns parallel, distributed memory processes).

TAU

Enter TAU, another excellent profiler (from the CS department of Oregon University: http://www.cs.uoregon.edu/research/tau/home.php). The benefits that TAU has to offer include the ability to profile threaded and MPI codes. There are several modules to choose from on bluecrystal.

On BCp1:

> module av tools/tau tools/tau-2.21.1-intel-mpi tools/tau-2.21.1-openmp tools/tau-2.21.1-mpi

On BCp2:

> module add profile/tau profile/tau-2.19.2-intel-openmp profile/tau-2.19.2-pgi-mpi profile/tau-2.19.2-pgi-openmp profile/tau-2.21.1-intel-mpi

For example, let's add the version of TAU on BCp2 that will use the Intel compiler and can profile threaded code:

> module add profile/tau-2.19.2-intel-openmp

Once I have it the module loaded, I can compile some C code using the special compiler wrapper script, tau_cc.sh:

tau_cc.sh -O3 d2q9-bgk.c -o d2q9-bgk.exe

Much like gprof, appropriately instrumented code will write out profile information as a side-effect (again you're program will likely be slowed as a consequence), which we can read using the supplied pprof tool

> pprof

Reading Profile files in profile.*

NODE 0;CONTEXT 0;THREAD 0:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%Time Exclusive Inclusive #Call #Subrs Inclusive Name

msec total msec usec/call

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

100.0 21 2:00.461 1 20004 120461128 int main(int, char **) C

91.5 58 1:50.231 10000 40000 11023 int timestep(const t_param, t_speed *, t_speed *, int *) C

70.8 1:25.276 1:25.276 10000 0 8528 int collision(const t_param, t_speed *, t_speed *, int *) C

19.8 23,846 23,846 10000 0 2385 int propagate(const t_param, t_speed *, t_speed *) C

8.3 10,045 10,045 10001 0 1004 double av_velocity(const t_param, t_speed *, int *) C

0.8 1,016 1,016 10000 0 102 int rebound(const t_param, t_speed *, t_speed *, int *) C

0.1 143 143 1 0 143754 int write_values(const t_param, t_speed *, int *, double *) C

0.0 34 34 10000 0 3 int accelerate_flow(const t_param, t_speed *, int *) C

0.0 18 18 1 0 18238 int initialise(t_param *, t_speed **, t_speed **, int **, double **) C

0.0 0.652 0.652 1 0 652 int finalise(const t_param *, t_speed **, t_speed **, int **, double **) C

0.0 0.002 0.572 1 1 572 double calc_reynolds(const t_param, t_speed *, int *) C

To view the results of running an instrumented, threaded program we again use pprof, and are presented with profiles for each thread and an average of all threads:

[ggdagw@bigblue2 example2]$ pprof

Reading Profile files in profile.*

NODE 0;CONTEXT 0;THREAD 0:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%Time Exclusive Inclusive #Call #Subrs Inclusive Name

msec total msec usec/call

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

100.0 0.077 94 1 1 94201 int main(void) C

99.9 0.042 94 1 1 94124 parallel fork/join [OpenMP]

99.9 94 94 4 3 23520 parallelfor [OpenMP location: file:reduction_pi.chk.c <26, 30>]

99.3 0.001 93 1 1 93565 parallel begin/end [OpenMP]

99.3 0 93 1 1 93546 for enter/exit [OpenMP]

2.6 0.002 2 1 1 2404 barrier enter/exit [OpenMP]

NODE 0;CONTEXT 0;THREAD 1:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%Time Exclusive Inclusive #Call #Subrs Inclusive Name

msec total msec usec/call

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

100.0 0 93 1 1 93047 .TAU application

100.0 0.001 93 1 1 93047 parallel begin/end [OpenMP]

100.0 93 93 3 2 31015 parallelfor [OpenMP location: file:reduction_pi.chk.c <26, 30>]

100.0 0.001 93 1 1 93045 for enter/exit [OpenMP]

2.4 0.005 2 1 1 2214 barrier enter/exit [OpenMP]

NODE 0;CONTEXT 0;THREAD 2:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%Time Exclusive Inclusive #Call #Subrs Inclusive Name

msec total msec usec/call

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

100.0 0 92 1 1 92069 .TAU application

100.0 0.001 92 1 1 92069 parallel begin/end [OpenMP]

100.0 92 92 3 2 30689 parallelfor [OpenMP location: file:reduction_pi.chk.c <26, 30>]

100.0 0.001 92 1 1 92067 for enter/exit [OpenMP]

0.0 0.004 0.011 1 1 11 barrier enter/exit [OpenMP]

NODE 0;CONTEXT 0;THREAD 3:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%Time Exclusive Inclusive #Call #Subrs Inclusive Name

msec total msec usec/call

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

100.0 0 92 1 1 92947 .TAU application

100.0 0.001 92 1 1 92947 parallel begin/end [OpenMP]

100.0 92 92 3 2 30982 parallelfor [OpenMP location: file:reduction_pi.chk.c <26, 30>]

100.0 0.001 92 1 1 92945 for enter/exit [OpenMP]

1.9 0.002 1 1 1 1783 barrier enter/exit [OpenMP]

FUNCTION SUMMARY (total):

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%Time Exclusive Inclusive #Call #Subrs Inclusive Name

msec total msec usec/call

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

100.0 372 372 13 9 28626 parallelfor [OpenMP location: file:reduction_pi.chk.c <26, 30>]

99.8 0.004 371 4 4 92907 parallel begin/end [OpenMP]

99.8 0.003 371 4 4 92901 for enter/exit [OpenMP]

74.7 0 278 3 3 92688 .TAU application

25.3 0.077 94 1 1 94201 int main(void) C

25.3 0.042 94 1 1 94124 parallel fork/join [OpenMP]

1.7 0.013 6 4 4 1603 barrier enter/exit [OpenMP]

FUNCTION SUMMARY (mean):

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%Time Exclusive Inclusive #Call #Subrs Inclusive Name

msec total msec usec/call

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

100.0 93 93 3.25 2.25 28626 parallelfor [OpenMP location: file:reduction_pi.chk.c <26, 30>]

99.8 0.001 92 1 1 92907 parallel begin/end [OpenMP]

99.8 0.00075 92 1 1 92901 for enter/exit [OpenMP]

74.7 0 69 0.75 0.75 92688 .TAU application

25.3 0.0192 23 0.25 0.25 94201 int main(void) C

25.3 0.0105 23 0.25 0.25 94124 parallel fork/join [OpenMP]

1.7 0.00325 1 1 1 1603 barrier enter/exit [OpenMP]

perfExpert

If you are fortunate to be working on a Linux system with kernel version 2.6.32 (or newer), you can make use of perfExpert (from the Texas Advanced Computing Center, http://www.tacc.utexas.edu/perfexpert/quick-start-guide/). This gives us convenient access to a profile of cache use within our program.

A sample program is given on the TACC website. The code is below (I increased the value of n from 600 to 1000, so that the resulting example would show many L2 cache misses on my desktop machine):

source.c:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#define n 1000

static double a[n][n], b[n][n], c[n][n];

void compute()

{

register int i, j, k;

for (i = 0; i < n; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < n; j++) {

for (k = 0; k < n; k++) {

c[i][j] += a[i][k] * b[k][j];

}

}

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

register int i, j, k;

for (i = 0; i < n; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < n; j++) {

a[i][j] = i+j;

b[i][j] = i-j;

c[i][j] = 0;

}

}

compute();

printf("%.1lf\n", c[3][3]);

return 0;

}We can compile the code in the normal way:

gcc -O3 source.c -o source.exe

Next, we run the resulting executable through the perfexpert_run_exp tool, so as to collate statistics from several trial runs:

perfexpert_run_exp ./source.exe

Now, we can read the profile data using the command:

perfexpert 0.1 ./experiment.xml

which in turn shows us the extent of the cache missing horrors:

gethin@gethin-desktop:~$ perfexpert 0.1 ./experiment.xml Input file: "./experiment.xml" Total running time for "./experiment.xml" is 5.227 sec Function main() (100% of the total runtime) =============================================================================== ratio to total instrns % 0.........25...........50.........75........100 - floating point : 0 * - data accesses : 38 ****************** * GFLOPS (% max) : 0 * - packed : 0 * - scalar : 0 * ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- performance assessment LCPI good......okay......fair......poor......bad.... * overall : 2.0 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> upper bound estimates * data accesses : 8.0 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>+ - L1d hits : 1.5 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> - L2d hits : 2.7 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>+ - L2d misses : 3.8 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>+ * instruction accesses : 8.0 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>+ - L1i hits : 8.0 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>+ - L2i hits : 0.0 > - L2i misses : 0.0 > * data TLB : 2.1 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> * instruction TLB : 0.0 > * branch instructions : 0.1 >> - correctly predicted : 0.1 >> - mispredicted : 0.0 > * floating-point instr : 0.0 > - fast FP instr : 0.0 > - slow FP instr : 0.0 >

Valgrind

Valgrind is an excellent open-source tool for debugging and profiling.

Compile your program as normal, adding in any optimisation flags that you desire, but also add the -g flag so that valgrind can report useful information such as line numbers etc. Then run it through the callgrind tool, embedded in valgrind:

valgrind --tool=callgrind your-program [program options]

When your program has run you find a file called callgrind.out.xxxx in the current directory, where xxxx is replaced with a number (the process ID of the command you have just executed).

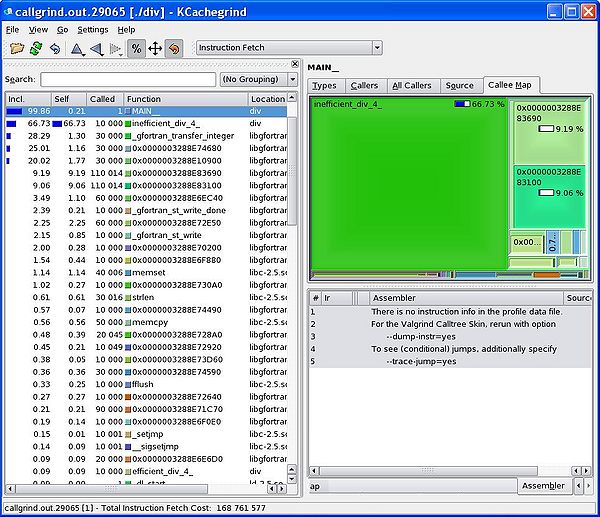

You can inspect the contents of this newly created file using a graphical display too call kcachegrind:

kcachegrind callgrind.out.xxxx

(For those using Enterprise Linux, you call install valgrind and kcachegrind using yum install kdesdk valgrind.)

A Simple Example

svn co https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/profiling/trunk ./profiling cd profiling/examples/example1 make valgrind --tool=callgrind ./div.exe >& div.out kcachegrind callgrind.out.xxxx

We can see from the graphical display given by kcachegrind that our inefficient division routine takes far more of the runtime that our efficient routine. Using this kind of information, we can focus our re-engineering efforts on the slower parts of our program.

The Matlab Profiler

- See http://www.mathworks.co.uk/help/matlab/ref/profile.html

- See also tic, toc timing: http://www.mathworks.co.uk/help/matlab/ref/tic.html

The Python Profiler

- http://www.huyng.com/posts/python-performance-analysis/

- http://www.appneta.com/2012/05/21/profiling-python-performance-lineprof-statprof-cprofile/

OK, but how do I make my code run faster?

OK, let's assume that we've located a region of our program that is taking a long time. So far so good, but how can we address that? There are--of course--a great many reasons why some code may take a long time to run. One reason could be just that it has a lot to do! Let's assume, however, that the code can be made to run faster by applying a little more of the old grey matter. With this in mind, let's consider a few common examples of code which can tweaked to run faster.

Compiler Options

You probably want to make sure that you've added all the go-faster flags that are available before you embark on any profiling. Activating optimisations for speed can make your progam run a lot faster!

As mentioned earlier, see e.g. https://www.acrc.bris.ac.uk/pdf/compiler-flags.pdf, for tips on which options to choose.

gcc d2q9-bgk.c -o d2q9-bgk.exe

time ./d2q9-bgk.exe

real 4m34.214s user 4m34.111s sys 0m0.007s

gcc -O3 d2q9-bgk.c -o d2q9-bgk.exe

real 2m1.333s user 2m1.243s sys 0m0.011s

gcc -O3 -ffast-math d2q9-bgk.c -o d2q9-bgk.exe

real 1m9.068s user 1m8.856s sys 0m0.012s

Scripting Languages

- Avoid loops, especially in interpreted languages (like R).

Heed the Memory Hierarchy

- Avoid touching files on the disk, e.g. 'lock files'.

A Common Situation Involoving (Fortran) Loops

For our first example, consider the way we loop over the contents of a 2-dimensional array--a pretty common situation!. Skip over a directory and compile the example programs:

cd ../example2 make

In this directory, we have two almost identical programs. Compare the contents of loopingA.f90 and loopingB.f90. You will see that inside each program a 2-dimensional array is declared and two nested loops are used to visit each of the cells of the array in turn (and an arithmetic value is dropped in). The only way in which the two programs differ is the order in which the cycle through the contents of the arrays. In loopingA.f90, the outer loop is over the columns of the array and the inner loop is over the rows (i.e. for a given value of ii, all values of jj and cycled over). The opposite is true for loopingB.f90.

Let's compare how long it takes these two programs to run. We can do this using the Linux time command:

time ./loopingA.exe

and now,

time ./loopingB.exe

Dude! loopingA.exe takes more than twice the time of loopingB.exe. What's the reason?

Well, Fortran stores it's 2-dimensional arrays in column-major order. Our 2-dimension array is actually stored in the computer memory as a 1-dimension array, where the cells in a given column are next to each other. For example, the array:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & 5 & 6 \end{bmatrix} }[/math]

would actually be stored in memory as:

1 4 2 5 3 6

That means is that our outer loop should be over the columns, and our inner loop over the rows. Otherwise we would end up hopping all around the memory, which takes extra time, and explains why loopingA takes longer.

The opposite situation is true for the C programming language, which stores its 2-dimensional arrays in row-major order. You can type:

make testC

To run some equivalent C code examples.

Avoid Expensive Operations

- Anything in interpreted languages, especially loops.

- memory operations such as allocate in Fortran, or malloc in C

- sqrt, exp and log

- division and raising raising numbers to a power