Difference between revisions of "CtoC++"

| Line 417: | Line 417: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| − | '''inheritance.h''' | + | In '''inheritance.h''', we see a simple base class declared: |

<pre> | <pre> | ||

| Line 438: | Line 438: | ||

}; | }; | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Followed by a derived class which builds on the concept of a celestial body and adds in space to store information about it's orbit and additional methods: | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

| Line 458: | Line 460: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| − | '''main.cc''' | + | In '''main.cc''', we see that through the process of inheritance, we can call the '''volume()''' method (declared in the base class) from an instance of the derived class: |

<pre> | <pre> | ||

Revision as of 12:26, 7 September 2009

CtoC++: Upgrading to Object Oriented C

Introduction

This tutorial carries on where StartingC left off.

To get the material, cut and paste the contents of the box below onto your command line.

svn co http://source.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/CtoC++/trunk ./CtoC++

In this tutorial we will assume basic linux skills as outlined in Linux1.

Cutting to the Chase: Classes and Encapsulation

So, he we are contemplating C++. We've got to grips with most of the C language in StartingC and it looked alright. Definitely serviceable. What's all the fuss about C++? Well, I believe that most of the fuss is about encapsulation. We saw the benefit of collecting together related variables into structures in C, true? Well, C++ goes further and allows us to collect together not only related variables, but also functions which use those variables too. An instance of a class is called an object and it comes preloaded with all the variables and functions (aka methods) that you'll need when considering said object.

What may have seemed like the relatively small enhancement of adding methods to the encapsulation has, in fact, resulted in a sea-change. No longer are we thinking about a program in terms of the variables and the functions, but instead we're thinking about objects (planets, radios, payrolls and the like) and how they interact with other objects. The whole thing has become far more modular, and so easier to work with. Indeed, this is no accident as object oriented programming (OOP) arose in response to programs written in the functional style getting larger and unwieldy and hard to work with. In short it arose to swap spaghetti for lego.

OK, enough of the spiel, let's get going with an example:

cd CtoC++/examples/example1 make

The first chunk of code to greet you inside class.cc (we'll use .cc to denote C++ source code files) is:

//

// This is a C++ comment line

//

#include <iostream> // A useful C++ library

#include <cmath> // The standard C math library

// declare a namespace in which to keep

// some handy scientific constants

namespace scientific

{

const double pi = 3.14159265; // note the use of 'const'

const double grav_constant = 6.673e-11; // uinversal graviational constant (m3 kg-1 s-2)

const int sec_per_day = 86400; // number of seconds in 24 hours

}

// avail ourselves of a couple of namespaces

// via the 'using' directive

using namespace std; // allows us to use 'cout', for example

using namespace scientific;

What's new? Well, first up, we see that the comment syntax has changed and that we can use just a leading double forward slash (//) to signal a note from the author. #include is familiar, except that we've dropped the .hs from inside the angle brackets.

The next block is a namespace declaration. The concept of a namespace is common to a number of programming languages and here we're setting one up called scientific and using it to store some handy constants. We can enclose anything we like in a namespace. We access the contents of a namespace via the using directive. In this case we're accessing an intrinsic one called std (standard)--we'll be doing that a lot!--and also our scientific one. The idea behind namespaces is to reduce the risk of a clash of names when programs get large. They're handy.

Next up in the source code is the class declaration (and definition, as it heppens) itself:

class satellite

{

private:

// Private members of a class class cannot be accessed

// from outside the class.

double period; // time taken to orbit e.g. earth (s)

double sma_of_orbit; // semi-major axis of satellite's orbit (m)

public:

// Public members of the class are visible to the

// rest of the program.

// Method to assign values to private variables.

void set(const double prd, const double sma)

{

period = prd;

sma_of_orbit = sma;

}

// Method to compute mass of a celestial body

// given the period of a satellite which orbits

// it and the semi-major axis of that orbit.

// See Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

double mass_of_attractor(void)

{

return (4.0 * pow(sma_of_orbit,3) * pow(pi,2)) / (pow(period,2) * grav_constant);

}

};

You can see that the class called satellite contains some variables and also some methods. The contents of the class is also separated into two sections by the keywords private and public. We've declared our variables to be private (cannot be seen from outside the class) and our methods to be public (are visible from outside). In doing so, we've set up an interface (i.e. the public methods) through which other parts of the program can interact with this class. In this case, the program at large can call set(), providing information about the satellite's orbit as it does so, and also mass_of_attractor() in order to discover the mass of whatever the satellite is orbiting.

The existence of an interface simplifies the ways in which the object interacts with the rest of the program and means that any alterations to the program are much easier to make. For example, any you can make changes to the internals of a class without fear that you will unwittingly break some aspect of the program outside of the interface. Indeed, we could entirely re-write the contents of a (perhaps complex) class and as long as the interface remains unchanged, the rest of the program need never know! This is quite a boon for scientific software, which has a more rapid schedule of alterations that other kinds of software.

Last up is our glue code, or main function:

int main (void)

{

// Declare an 'instance' of the satellite class,

// called 'moon'.

satellite moon;

cout << "== Welcome to the intro to classes program! ==" << endl << endl;

// Set some values pertaining to the moon.

moon.set((27.322*sec_per_day),384399e3);

// Call a method of the satellite class

// and report results to the 'stdout' stream.

cout << "Mass of the Earth (kg) is: "<< moon.mass_of_attractor() << endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

in which we declare in instance of our satellite class, the moon object, call set() and finally mass_of_attractor(), noting the dot (.) operator for accessing members of the class.

The way in which we print to stdout is also different in C++. Here we have used the left shift operator (<<) together with the cout I/O stream and also the endline (endl) operator.

You can run the program--and weigh the Earth!--by typing:

./class.exe

(The eagle-eyed amongst you will note that we have a small error in our calculation of mass. The intrigued amongst the cohort of eagles may be relieved to see that Kepler's law gives the combined mass of the moon and Earth in this case, and that if we subtract off the mass of the moon, we get closer to the actual mass of the Earth--phew!)

Exercises

- Add a new method to the satellite class to compute the mean orbital speed of the satellite, and perhaps another to compute the satellites speed at various points along it's orbit?

- Add a whole new class to the program. One for a planet orbiting a star, such as our sun, would be a good one.

More on Methods

OK, so far so good. We've bundled up some methods and variables into a class. This is all to the good. However, we haven't delved too deeply into all the features that C++ provides with regards to methods. Let's rectify that right now. We'll make a start by typing:

cd ../example2 make

In this directory, you'll see that we've split our program over the files;

- methods.h, containing the declarations for our enhanced satellite class,

- methods.cc, containing the 'meat' of the methods and,

- main.cc, containing the main function inside which we run our class through it's paces.

Looking inside the header file, you'll see our scientific namespace again, as well as the class declaration:

class satellite

{

private:

char *name; // name of satellite

unsigned int iNameLen; // length of name string

double period; // time taken to orbit e.g. earth (s)

double sma_of_orbit; // semi-major axis of satellite's orbit (m)

// copy method

void copy(const satellite& _stllt);

public:

// default constructor

// Note same name as class

satellite();

// constructor with arguments

satellite(const char *nm, const double prd, const double sma);

// copy construcor

satellite(const satellite& _stllt);

// assignment operator

satellite& operator=(const satellite& _stllt);

// previous mass calculation method

double mass_of_attractor(void);

// previous set method

void set(const char *nm, const double prd, const double sma);

// display method

void display(void);

// default destructor

~satellite();

};

This time around we have some extra class members:

- We have a character pointer called name, along with an integer to store the length of the character array, once some memory has been allocated.

- We have a number of constructors methods, which we immediately see are special since their shared name matches the name of the class.

- We have a destructor, where it's name has a leading twiddle (~) and also matches the class name.

- We have a private method called copy,

- a display method and also

- an assignment operator (=).

Let's go through these in turn.

Constructors are invoked when a new object is created. The two relevant lines in 'main.cc are:

satellite moon1; // default construcor

satellite moon2("moon2",(27.322*sec_per_day),384399e3); // construcor with args

Here we've declared two instances of the satellite class, and called them moon1 and moon2. We created moon1 using the default constructor (no arguments follow the variable name). The internals of which we can find inside methods.cc:

// default constructor

satellite::satellite()

{

iNameLen = 0;

name = new char[iNameLen + 1];

(*name) = '\0'; // empty string

period = 0.0;

sma_of_orbit = 0.0;

}

As it's name suggests, this method sets up a default object (zero values, null strings etc.) in lieu of any specific information.

moon2 was created using a constructor which takes arguments:

// constructor with arguments

satellite::satellite(const char *nm, const double prd, const double sma)

{

set(nm, prd, sma);

}

This method accepts the name of the satellite instance, together with values for the period and the semi-major axis. Given these, it merely calls the set() method, which is sensible since this method has all the functionality that we desire, and it's a bad idea to duplicate the code.

We can see that these two methods have exactly the same save and differ only in their associated argument lists. This is an example of what's called overloading, which can be highly desirable when designing clear and simple class interfaces. We can overload both methods and operators.

You will see that we also have what we've labelled as a copy constructor, which takes another instance of the satellite class as it's argument and creates another in it's image.

// copy constructor

satellite::satellite(const satellite& _stllt) : name(NULL) {copy(_stllt);}

This method makes use of a member initializer and calls the private copy method (not available from outside the class, but callable from other members). Member initializers are carried out before the method itself is called and are always done in order. In this case, we've set name equal to NULL so as to avoid some unnecessary dynamic memory allocation manoeuvres in the copy method.

C++ will provide what's known as shallow copy constructor, assignment and destructor methods implicitly, which are fine for classes which do not make use of dynamic memory allocation. However, for more complex classes, we must write our own deep copying methods. For example, our copy method:

void satellite::copy(const satellite& _stllt)

{

if (name != NULL) {

delete[] name;

}

iNameLen = _stllt.iNameLen;

name = new char[iNameLen + 1];

strcpy(name,_stllt.name);

period = _stllt.period;

sma_of_orbit = _stllt.sma_of_orbit;

}

The copy needs to be deep, as if we were not careful, we would end up with two classes containing pointers to the same block of memory (holding the 'name' character array) and that would not be at all what we wanted! Instead we allocate some new memory and call a string copying method from the standard C library. Copying the values of the numerical variables is easy. We've made use of the new C++ memory allocation function new, which we can all agree are far simpler than 'malloc()'. Correspondingly delete replaces 'free()'.

None of the other methods warrant any comment, except for the assignment operator:

satellite& satellite::operator=(const satellite& _stllt)

{

// assignment to self test

if (this == &_stllt) {

return (*this);

}

else {

copy(_stllt);

}

return (*this);

}

In this case, we've overloaded the = operator and given it particular instructions when faced with instances of the satellite class on either side of it, such as the statement:

moon1 = moon2;

Using this method, we've ensured that a deep copy takes place, where the name string is handled appropriately.

Good eh? Now we see the way to create full and convenient interfaces to our classes. To run the program, type:

./methods.exe

Exercises

- Method arguments can have defaults attached, e.g. satellite(const double period = 0.0, ...). Rewrite our constructor with arguments, so that we no longer need a default constructor.

- Experiment with the copy constructor. For example, it is legal syntax to add the declaration satellite moon3(moon2); towards the end of the main function.

- Can you define other methods/operators for this class. How about 'less than' (<) or 'greater than' (>) operators. If two satellites were to collide and coalesce, what could a plus (+) operator do?...

Templates and the Standard Template Library

OK, so things are going swimmingly. We're using classes for encapsulation. We've considered the interface to a class in some detail and seen how we can improve the way that instances of a class interact with the rest of the program. This is all excellent, but.. you knew there was a wrinkle on the horizon, eh?

Let's take a moment to think about data structures. The way we store data can make a huge difference to a program. Given the right data structures, solving an involved problem can be a pleasure, if not a cinch. Given the wrong data structures, the whole enterprise can be miserable!

So far, we've hardly stopped to think about data structures. We've seen single variables and arrays of said variables. As an improvement, we've also seen structures and even arrays of structures. There are a great many more possibilities, however. We can have stacks, queues, linked lists, binary trees, sets, strings, vectors, matrices and many, many more. All these data structures are designed to highlight certain properties of some stored data and so make certain operations as easy as possible.

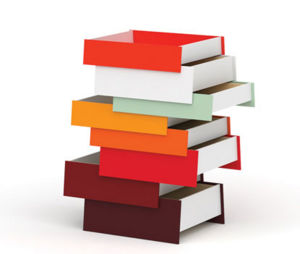

Let's consider one of the simpler structures--a stack--in this case, of boxes. So we take a box and set it down. We take another box and place it on top of the first, and so on. In order to get at the first box, we need to take all the other boxes off it. The image below shows such as stack.

Sometimes, this is exactly the way in which we want to store our data. If we we're modelling the deposition and erosion of sediments on the sea floor, for example, a stack would be just the ticket.

OK, ok, this is all well and good, but where's the wrinkle? Well, let's say we want a stack of real numbers at one point of a program, and a stack of integers at another. Does that mean that we would need to write two different classes, with all their associated interface gubbins, one for the doubles and one for the integers? That would be a pain!

Fear not! We can write a template class instead. Templates are neat, as we do not need to specify the type of thing that will be found in a stack until the point where we declare an instance of said stack. In order to illustrate this approach, we have a small example of what we will call a LIFO stack. LIFO stands for 'Last In, First Out'.

cd ../example3 make

Inside ifo.h, you'll see the declaration (and definition - many compilers seem to prefer this) of our template class:

template <class TYPE>

class Stack

{

private:

int size; // number of elements in stack

int head; // index of element in the head of the stack

TYPE* stackPtr; // pointer to the stack

public:

// constructor with default of 10 items in the stack

Stack(int = 10);

// destructor

~Stack() { delete[] stackPtr; }

// method for adding an item

bool push(const TYPE& item);

// method for removing an item

bool pop();

// method to report top item in stack

TYPE top();

// method to test if stack is empty

bool empty() const;

// method to test if stack is full

bool full() const;

};

Note the use of the wildcard name TYPE in the angle brackets (this name could be anything, but TYPE in capitols stands out nicely). The interface to the class contains methods for construction and destruction, as well as the basic modes of operation--pushing and poping items on and off the stack. We have a method to report what's on the top of the stack and a couple more to report whether the stack is full or empty.

Feel free to browse the details of the implementation, but we'll skip over them here. They are relatively rudimentary and no doubt could tolerate a good deal of improvement. The short piece of glue code is contained in main.cc and you can run the example program by typing:

./lifo.exe

One of the reasons, why we haven't laboured too hard over our stack implementation is because C++ provides us with something called the Standard Template Library, or STL, for short. This contains tried and tested implementations of of many data structures and algorithms that we would like. All there provided for us!

An example of using a stack from the STL is in:

cd ../example4 make

This time, all we need is in main.cc:

#include <iostream>

#include <stack>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

stack<char> charStack; // a stack of characters

stack<int> intStack; // a stack of integers

...

and you can run the program in the usual way:

./stack.exe

To learn more about the STL, you can take a look at, e.g. SGI's page or that on Wikipedia. O'Reilly, of course have a few good books on the topic too.

Inheritance

The last topic that we will look at is inheritance. This is a mechanism through which you can declare a new class--called the derived class--to be a specialisation of another class--called the base class. In line with the spirit of the pragmatic programming tutorials, we will not linger on this topic as we believe that while it is certainly neat, it is most likely of limited use in most scientific projects.

In this example, we will consider the simplest, but quite likely the most often used, form on inheritance--public inheritance from a single parent base class.

cd ../example5 make

In inheritance.h, we see a simple base class declared:

class celestial_body

{

private:

double equitorial_radius;

double polar_radius;

public:

// Note, not using a constructor...

// a set method instead, which we can use to access

// variables from the derived class.

void set(const double eq_rad, const double pol_rad);

// volume

double volume(void) const;

};

Followed by a derived class which builds on the concept of a celestial body and adds in space to store information about it's orbit and additional methods:

class satellite : public celestial_body

{

private:

double period;

double sma_of_orbit;

public:

// constructor

satellite(const double prd = 0.0, const double sma = 0.0,

const double eq_rad = 0.0, const double pol_rad = 0.0);

// mass

double mass_of_attractor(void) const;

};

In main.cc, we see that through the process of inheritance, we can call the volume() method (declared in the base class) from an instance of the derived class:

cout << "Volume of moon2 (m^3) is: " << moon2.volume() << endl;

./inheritance.exe