Fortran1

Fortran1: The Basics

Getting the content for the practical

The examples are available via svn:

svn co https://svn.ggy.bris.ac.uk/subversion-open/fortran1/trunk fortran1

We'll use GCC and Intel Fortran compilers. You need to load these modules on phase 3:

module add languages/intel-compiler-16-u2 languages/gcc-7.1.0

Not one, Many!

That was fun. Back to thinking about variables for a moment:

cd ../example4

Last time we declared just one thing of a given type. Sometimes we're greedy! Sometimes we want more! To be fair, some things are naturally represented by a vector or a matrix. Think of values on a grid, solutions to linear systems, points in space, transformations such as scaling or rotation of vectors. For these sorts of things the kings and queens of Fortran gave us programmers arrays. Take a look inside static_array.f90:

real, dimension(4) :: tinyGrid = (/1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0/)

real, dimension(2,2) :: square = 0.0 ! 2 rows, 2 columns, init to all zeros

real, dimension(3,2) :: rectangle ! 3 rows, 2 columns, uninit

The syntax here reads, "we'll have an one-dimensional array (i.e. vector) of 4 reals called tinyGrid, please, and we'll set the initial values of the cells in that array to be 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 and 4.0, respectively.

For the second and third declarations, we're asking for two-dimensional arrays. One with two rows and two colums, called square, and one with three rows and two colums. We're calling that rectangle.

The program then goes on to print out the contents of tinyGrid.

If we want to access a single element of an array, we can do so by specifying it's indices:

write (*,*) "square(1,2) is the top right corner:", square(1,2)

Fortran provides a couple of handy intrinsic routines for determining the size (how many cells in total) and the shape (number of dimensions and the extent of each dimension) of an array.

write (*,*) "size(rectangle) gives total number of elements:", size(rectangle)

write (*,*) "shape(rectangle) gives rank and extent:", shape(rectangle)

Fortran also allows us to reshape an array on-the-fly. Using this intrinsic, we can copy the values from tinyGrid into square. Neat.

square = reshape(tinyGrid,(/2,2/))

Fortran also provides us with a rather rich set of operators (+, -, *, / etc.) for array-valued variables. Have a go at playing with these. If you know some linear algebra, you're going to have a great time with this example!

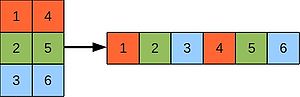

One thing to bear in mind when we consider 2D arrays is that Fortran stores them in memory as a 1D array and 'unwraps' them according to column-major order:

Exercises

- Create 3x3 grid to store the outcome of a game of noughts-and-crosses (tic-tac-toe), populate it and print the grid to screen.

- Fortran allows you to slice arrays. For example the second column of the 2d-array 'a' is a(:,2). Print the third row from the grid above.

- Add two vectors together. Is this algebraically correct? What about adding two matrices?

- Create two 2-d arrays. Populate one randomly and create another as a mask. Combine the two matrices and print the result.

The static malarky is because Fortran also allows us to say we want an array, but we don't know how big we want it to be yet. "We'll decide that at run-time", we programmers say. This can be handy if you're reading in some data, say a pay-roll, and you don't know how many employees you'll have from one year to the next. Fortran calls these allocatable arrays and we'll meet them in Fortran2.

If Things get Hectic, Outsource!

cd ../example5Now, as we get more ambitious, the size of our program grows. Before long, it can get unwieldy. Also we may find that we repeat ourselves. We do the same thing twice, three times. Heck, many times! Now is the time to start breaking your program into chunks, re-using some from time-to-time, making it more manageable. Fortran gives us two routes to chunk-ification, functions and subroutines.

Let's deal with subroutines first. In procedures.f90, scroll down a bit and you can see:

subroutine mirror(len,inArray,outArray)

implicit none

! dummy variables

integer, intent(in) :: len

character,dimension(len),intent(in) :: inArray

character,dimension(len),intent(out) :: outArray

! local variables

integer :: ii

integer :: lucky = 3 ! notice scope of this identically named variable

do ii=1,len

outArray(len+1-ii) = inArray(ii)

end do

write (*,*) "'lucky' _inside_ subroutine is:", lucky

end subroutine mirror

Now, note that this is outside of the main program unit. (In principle, we could hive this off into another source code file, but we'll leave that discussion until Fortran2.) Notice also that we have a shiney implicit none resplendent at the top of the subroutine. Overall, it looks pretty similar to how a main program unit might look, but with the addition of arguments. Those fellows in the parentheses after the subroutine name. The declaration part also lists those arguments and we've commented that this are so-called dummy variables. We also see an attribute that we've not seen before, called intent. This is a very handy tool for defensive programming (remember aka bug avoidance). Using intent we can say that the integer len is an input and as such we're not going to try to change it. Likewise for the charcter array inArray. It would be a compile-error if we did. We also state that the character array outArray is an output and we're going to give it a new value come what may! We also have some variables that are local. Interestingly enough, one of our local variables, the integer called lucky, has exactly the same name as a variable in the main program unit. When we run the program, however, we will see that the two do not interfere with each other. This is down to their scope. The scope of lucky in the main program is all and only the main program unit and the scope of lucky in the subroutine is all and only the subroutine. We say that the main program unit and the subroutine units have different name spaces.

Well, we've seen a lot of new syntax and concepts in all that. Useful ones though. This program is small and artificial, so it's hard to see the benefits just yet. You will, however, as your programs grow. The subroutine is called from the main program , funnily enough by a call statement. Notice how the arguments passed to the subroutine in the call statement also have different names in the main program and the subroutine. That's scope again.

Functions similar yet different to subroutines. Notice that we don't call them in the same way. We still pass arguments, but the functions returns and value, and so we could place a function on the right-hand side (RHS) of an assignment. Typically we would write a function for a smaller body of work. We can potentially invoke it in a neater way from our main program, however.

Looking at the body of the function:

function isPrime(num)

implicit none

! return and dummy variables

logical :: isPrime

integer, intent(in) :: num

select case (num)

case (2,3,5,7,11,13,17,19,23,29)

isPrime = .true.

case default

isPrime = .false.

end select

end function isPrime

we can see that we have a declaration for a variable with the same name as the function. The type of this variable is the return type of the function. Indeed the value of this variable when we reach the bottom of the function is the value passed by to the calling routine. Note that we can call functions and subroutines from other functions and subroutines etc. in a nested fashion.

The last thing of note is the funky interface structure at the top of the main program:

interface

function isPrime(num)

logical :: isPrime

integer, intent(in) :: num

end function isPrime

end interface

Our function definition is outside of the main program and so is said to be external. The main program unit needs to know about it, however, and an interface structure is a good way to do this as it prompts Fortran to check that all the arguments match up between the call and the definition. It's the way to do it..for now. (We'll meet Fortran modules in Fortran2, which will give us a neater way to perform the same checks.)

Try running the program and writing some functions and subroutines of your own.

Exercises

- Write a simple error handling subroutine that stops the program after printing a message, which is passed in as an argument.

- Does the surface area of a circle increase linearly with an increase in radius? How about circumference? Write some functions and a loop to investigate.

- What happens if you write a function which calls itself?

Input and output

OK, say we want some permenance? Perhaps we want to record the outputs of our program for some time, or we want to read the same values into a program each time that we run it. Storing data in files is the way to go.

File i/o

cd ../example6

In this example we'll see how to read and write data to and from files. The code for this example in contained in file_access.f90.

Before we can either read from- or write to- a file, we must first open it. Funnily enough, we can do this using the open statement, e.g.:

open(unit=19,file="output.txt",form='formatted',status='old',iostat=ios)

- unit is a positive integer given to the file so that we can refer to it later. Several numbers are reserved, however, so we must avoid 5 (keyboard), 6 (screen), 101 (stdout) & 102 (punch card!).

- file is a character string (can be 'literal') containing the name of the file to open.

- form is the file format--'formatted' (text file) or 'unformatted' (binary file).

- status specifies the behaviour if the file exists:

- old the file must exists

- new the file cannot exists prior to being opened

- replace the old file will be overwritten

- iostat is a non-zero integer in case of an error, e.g. the file cannot be opened for instance.

When you have finished with a file, you must close it:

close(19)

Note that if you need to go back to the beginning of a file, you don't have to close it and open it again, you can rewind it:

rewind(19)

To write to a file, the syntax is, e.g.:

write(unit=19,fmt=*) array1, array2

where,

- array1 & array2 are variables we wish to write to the file.

- unit is the unit number of the file we want write to.

- fmt is a format string. We have chosen '*', which gives us default settings. However, we can gain greater control by specifying in detail what we will be writing and how we would like it formatted. Take a look in the example file_access.f90 for examples.

Similarly, we use a read statement to extract data from a file, e.g.:

read(unit=19,fmt=*,iostat=ios) var1, var2

Note is that it is very important to use the iostat attribute to make sure that we handle any errors, and don't press on regardless into oblivion! e.g.:

if (ios /= 0) then

print*,'ERROR: could not open file'

stop

end if

Among other things, the program file_access.exe writes the same data to; (i) a text file; and (ii) a binary file:

open(unit=56,file='output.txt',status='replace',iostat=ios,form='formatted')

if (ios /= 0) then

print*,'ERROR: could not open output.txt'

stop

end if

open(unit=57,file='output.bin',status='replace',iostat=ios,form='unformatted')

if (ios /= 0) then

print*,'ERROR: could not open output.bin'

stop

end if

! write size1 and size2 to output files (and then compare sizes)

write(57) array1

write(57) array2

close(57)

write(56,*) array1

write(56,*) array2

close(56)

If you do a long listing('ls -l'), you'll see the size difference:

-rw-r--r-- 1 fred users 220032 Feb 8 11:01 output.bin -rw-r--r-- 1 fred users 825002 Feb 8 11:01 output.txt

Using character strings as file names

cd ../example7

filename.f90 in example7 shows a little trick for people who output a lot of data and need to manipulate a lot of files. It is possible to use a write statement to output a number (or anything else) to a character string and to subsequently use that string as a filename to open, close and output to many files on the fly:

character(len=8) :: filename

integer :: ii, ios

! define a format to write a filename

10 format('output',i2.2)

do ii=1,20

write (unit=filename,fmt=10) ii

open(20,file=filename,status='replace',form='formatted',iostat=ios)

...

Namelists

And all of a sudden, we're at our last example:

cd ../example8

In namelists.f90, we'll look at another approach to file input and output. Fortran provides a way of grouping variables together into a set, called a namelist, that are input or output from our program en masse. This is a common situation. For example, reading in the parameters into a model. The statement:

namelist /my_bundle/ numBooks,initialised,name,vec

sets it up.

Fortran further provides us with built-in mechanisms for reading or writing a namelist to- or from a file.

First, we must open the file of course:

open(unit=56,file='input.nml',status='old',iostat=ios)

if (ios /= 0) then

print*,'ERROR: could not open namelist file'

stop

end if

Note that we made sure to tell Fortran that this is an old file, i.e. that it already exists, and to check the error code. I the case that the open operation failed, we've asked the program to halt with an error.

Now, assuming that we've opened the file OK, we proceed to read its contents. Fortran makes this rather easy for us, given that the information is contained in a namelist:

read(UNIT=56,NML=my_bundle,IOSTAT=ios)

if (ios /= 0) then

print*,'ERROR: could not read example namelist'

stop

else

close(56)

end if

In the read statement, we told fortran that we wanted to read a namelist and that the group of variables should be flagged in the file as my_bundle. Again we've checked the error status and decided to halt with an error should the read statement fail for any reason. Take a look at the contents of input.nml. See that it is ascii text and that the variables (with their values) do not need to be listed in the same order in the file as they are in the program:

&my_bundle numBooks=6 vec=1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 initialised=.false. name='romeo' &end

The program procedes to print the values to screen, demonstrating that they have indeed come from the file, to assign new values to the variables and then to write the modified values to a new file, called modified.nml. Compare the two ascii text files. Try running the program a second time and you will receive an error, telling you that the output could not be written since a file called modified.nml exists and that we expressly stated that is was to be a new file. Delete modified.nml, try again and it will succeed. Try changing the namelist, values, filenames etc. Go for it, make a mess! You'll learn a lot from it:)

Exercises

- Write some code to read in a colour (red, blue, green etc.) from a namelist and then print out the names of all the railway engines (thomas, percy, gordon etc.) that match.

- Read in the dimensions of an ellipse from file and print out it's area.

To go further

The Pragmatic Programming course continues with Linux2, a look at some of the more advanced but very useful Linux concepts.

Now that you are getting familiar with Fortran, go a bit further by reading Fortran2.

A useful Fortran textbook is called Fortran 90 Programming by Ellis, Philips & Lahey. Take a look at the 'A Good Read?' page for more details.